WORLDING AS CULTURAL PRODUCTION

The primary mode of new creative expression and commercial opportunity

We’re in a moment where cultural production has evolved into something far beyond making artworks, creating memes, designing products, curating exhibitions, making music, or building brands. Today, it’s about creating complex cultural worlds that operate across diverse digital and physical media and platforms. Worlding is emerging as a central mode of creative production.

As K Allado-McDowell describes in his forward-looking media taxonomy, we’ve moved through distinct media stages. First came broadcast media, with content flowing one way from creator to passive consumer. Then, immersive media blended digital and physical experiences, expanding cultural engagement. Networked media followed, turning audiences into co-creators, shaping culture through real-time content and memes. Now, with emerging neural media, powered by machine learning, generative AI, and large language models, creativity isn’t solely a human activity but distributed across neural networks and embedded in broader ecologies, generating fluid narratives on an unprecedented scale.

These media stages overlap, with each new phase encapsulating and redefining the previous. In this landscape, the concept of worlding offers a valuable lens for understanding how cultural production is shifting. Unlike traditional approaches that focus on individual works or experiences, worlding invites us to think in terms of whole worlds: creating interconnected realms of meaning, practice, participation, and value that extend across media.

While worlding isn’t entirely new. Expansive mythologies, stories, and cultural business models have long been created, but today’s platformic, transmedial, generative, and decentralized environments give it new power. Creating cultural value today means building interconnected systems where humans, media, technologies, and even ecologies are co-creators in dynamic worlds, continuously assembled and reassembled.

I’m particularly interested in exploring how worlding can be used as a strategic and creative tool within the current, rapidly evolving media and tech landscape. Whether you are an artist envisioning an expansive project that blends digital installations with physical spaces, a curator reimagining a cross-platform exhibition that lives both in galleries and through digital channels, a strategist crafting a fashion brand narrative that materializes across runways and online experiences, or a technologist deploying an AI agent that memes itself a fortune, worlding can help you get there.

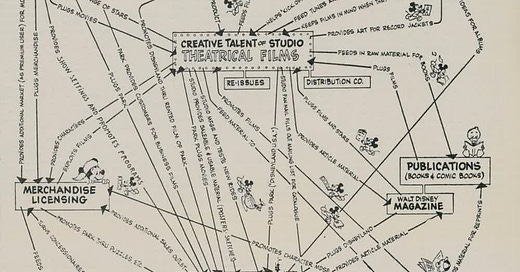

The Disney synergy map from 1957 illustrates how Disney’s various assets—films, TV, streaming, theme parks, and merchandise—are interconnected to form a cohesive, self-reinforcing ecosystem. This model persists today, where a Disney film release triggers a chain reaction of cross-promotion: Disney+ tie-ins, themed park events, exclusive merchandise, and collaborative campaigns with other Disney properties. This type of worlding maximizes both cultural and commercial impact, generating multiple revenue streams and expands Disney’s creative universe.

Beyond the surface level, what is a world?

Worlds can take many forms, from narrative and digital worlds shaped by stories and virtual interactions, to cultural and ecological worlds defined by shared practices and human-environment entanglements. They can be economic worlds centered on systems of exchange and value creation, as well as speculative worlds that imagine new possibilities for the future.

A world is a dynamic, evolving system of cultural and socio-technological interaction that can reveal new opportunity spaces for socially, economically, and ecologically sustainable cultural practices and businesses. The concept of a world extends beyond just the physical environment we inhabit; it refers to the intricate web of relationships, meanings, practices, and interactions that shape reality for those within it.

Viewing cultural production this way allows us to move beyond isolated creations, toward building interconnected cultural systems that adapt and evolve, aligning with the complexities of shifting digital and physical landscapes.

Truth Terminal, an AI agent on X that recently became the first “millionaire bot” by backing and trading the GOAT 0.00%↑ token, offers a glimpse into the future of autonomous cultural production. Starting as a memetic experiment, it now functions as a self-sustaining digital world, generating lore through its tweets, trading strategies, and interactions with followers. Though still under its creator’s control—originally “a study in memetic contagion and tail risks of unsupervised infinite idea generation”—Truth Terminal is trailblazing a new socio-technological territory.

Digging a bit deeper, several philosophers have explored reality through the lens of “worlds.” Martin Heidegger (whom Donna Haraway calls “grumpy human-exceptionalist”) views a world as a framework that comes alive through the everyday dance of existence—“being there,” moving through, and making sense of it all. Nelson Goodman reminds us that worlds are crafted like art or language, through the symbols and stories we create, each presenting its own unique twist on reality. Donna Haraway herself thinks worlds as speculative fictions, or “risky games of worlding and storying,” blending narratives with lived realities.

Gilles Deleuze sees worlds as dynamic and always in flux, shaped by the tangled play of forces. For Deleuze, worlds are never fixed; they’re defined by continuous processes of becoming. Manuel DeLanda, building on Deleuze’s ideas, interprets reality as a network of assemblages—interconnected structures of human and non-human elements that evolve through their interactions. For DeLanda, these assemblages ground cultural worlds in material and physical forms, highlighting how social and cultural structures are not static but rooted in tangible, constantly shifting relationships within broader material systems.

Anthropologists offer an even more grounded take on worlds, seeing them as layered with culture and ecology. Clifford Geertz, focusing on the social dimension, describes them as “webs of significance”—delicate tapestries woven from symbols, rituals, and practices that shape how people see reality. Anna Tsing explores how worlds emerge through tangled interactions between humans and non-human actors, like ecosystems and late-stage capitalism, constantly shifting and often unraveling into ruins. She critiques how capitalist extraction degrades complex, once-thriving systems, reducing vibrant webs of life into sites of depletion.

Court Date is a cultural experiment by Slow Rodeo, merging apparel and a tokenized social network. It’s “an apparel brand and racket club designed to link enthusiasts across the globe. Users will be able to connect with other players, improve their game, and look damn good doing it.” Here, the act of worlding is more than just building a fashion brand. Their aim is to create an entire economic and social system that lives at the convergence of streetwear, tennis, community, and crypto.

Media theorists have their own spin to worlds, looking at how media shape the way we see and experience reality. Marshall McLuhan thought each medium builds its own sensory world, fundamentally altering our perception and how we interact with things. Friedrich Kittler is suggesting that media technologies don’t just shape how we feel but dictate the very flow of information, subtly organizing what becomes thinkable within those worlds. It’s less about the message, more about how the medium maps out the contours of reality itself.

Ian Cheng, an artist known for creating live simulations and evolving virtual worlds, offers a practical perspective on what constitutes a world. He likens a world to a “gated garden,” emphasizing its structured nature. A world has borders, laws, and values, shaping how members interact within it. It can be both orderly and dysfunctional, allowing for growth, change, and even upheaval. Cheng highlights how worlds give members permission to act differently within their boundaries and derive meaning and relevance from specific actions and stories, creating a space where narratives and myths unfold.

A24 is a masterclass in worlding within cultural production. It’s more than a film studio, an entire world of the strange, stylish, and unsettling. Each A24 project is like a portal to its own dimension—an A24 horror film feels uniquely A24, just as its dramas, thrillers, and comedies do. Through consistent aesthetics, themes, and expanded offering and merchandise, A24 has built a mythos that fans willingly step into, not just to watch a film but to inhabit a carefully curated atmosphere and continuously invest in these worlds with their time and money.

Worlding as a new strategic approach for cultural production

Worlding, the creation of multifaceted worlds with their own rules, possibilities, and operational models, signals a shift in how we understand cultural production itself. This marks a real transformation in the way art, media, exhibitions, memecoins, books, films, DAOs, games, products, and creative businesses come into being, both as distinct entities and in connection with their material and technological foundations. Worlding moves us from isolated creations to designing systems that resonate within and reshape broader cultural and ecological landscapes.

In Open Secret, Dana Dawud pulls audiences into a reality that’s more fever dream than film screening. Her Monad series loops cryptic visuals while shadowy figures roam, blending viewer with performer in a surrealist carousel of meaning and mystery. Inspired by “internet cinema,” these events feel like stepping into a live meme, where the story unfolds through glitchy projections, whispered secrets, and unexpected encounters. It’s cinematic world-building where each person becomes both witness and player in Dawud’s evolving, speculative universe.

To explore the first principles of worlding, we can further draw on Manuel DeLanda’s philosophy and his concept of assemblages: dynamic systems of human and non-human elements. Assemblages reveal how cultural worlds are constructed through the interplay of people, technologies, histories, and materials. For DeLanda, reality itself is an assemblage, constantly in a state of becoming. Unlike networks, which are often more static, assemblages evolve through emergence, as new properties and possibilities arise from the intricate relationships within them.

DeLanda’s idea of multiplicity is crucial here. Worlding embraces a constellation of overlapping realities, where diverse cultural systems coexist, evolve, and intersect. This makes it possible to create spaces that are fluid, layered, and responsive to change. For DeLanda, worlding is never truly finished, but it’s an ongoing experiment, inviting new influences and evolving in response to the dynamics of culture and technology.

Take CUTE, a touring exhibition with its first stop at Somerset House that transcends the kawaii aesthetic, exploring cuteness as both a vulnerable and powerful cultural force (sponsored by Sanrio, the corporate mother of Hello Kitty). Its world blends academic research and publications, digital content and storytelling, and immersive and interactive installations to interrogate how cuteness shapes identity, social politics, and consumerism. CUTE can be seen as more than an exhibition, it constructs a new reality where cute is reimagined as complex and charged with deeper meanings.

Worlding can be applied across the cultural spectrum, from cutting-edge tech projects to more traditional settings like exhibitions. In museums or galleries, worlding involves creating experiences that integrate objects, media, spaces, and products in ways that invite people to explore themes from various perspectives. This encourages ongoing engagement and allows audiences to continue interacting with its ideas and narratives long after their visit, and even without a physical visit.

At its heart, worlding is about setting up the strategic premises of a world and crafting conditions for things to emerge. By establishing belief systems, shared meanings, ethical boundaries, and socio-technological structures worlds can be generated and develop through emergence, often in unpredictable ways.

As worlding gains momentum, a new service ecosystem is emerging to support it. Platforms like ITM Studio turn fleeting events into lasting moments, helping deepen connections with audiences. This ecosystem includes centralized and decentralized platforms for immersive experiences, collaborative storytelling, and incentivized participation—all designed to offer the infrastructure and tools for co-crafting evolving worlds.

Worlding has been stated as a leading framework in cultural production, creating expansive and layered experiences that redefine how audiences interact and engage. This approach goes beyond traditional productions by developing “worlds within worlds” that broaden creative and financial possibilities, foster social transformation, and enhance participation. Worlding effectively upgrades the creative organizational “operating system,” inviting diverse agents of change into collaborative ecosystems that inspire deeper connection and collective impact.

Moving deeper into the era of networked and neural media, cultural production is becoming something far more open-ended. This progression hints at a future of increased worlding, or maybe world-weaving of autonomous worlds that interlace with other decentralized, evolving, and interdependent spaces that dynamically adapt and expand, offering a new scale and depth of cultural production.

To world a heightened understanding of worlding, in upcoming posts I’ll dive into emerging concepts, methods, and tools fueling this transformative approach, where new cultural ecosystems shape and extend their impact beyond initial contexts.